Academics are alternately excited or full of ennui watching large language models spit out full research papers in the span of minutes. Economist Paul Novasad wrote a paper with AI in 3 hours and David Yanagizawa-Drott did something similar but without as much oversight.

Of course, these research papers are impressive technical demonstrations, but do not rise to the level of a fantastic contribution to economic literature. But still, I think for some (perhaps for many) they see the writing on the wall, our time will come, woe be unto us. If an AI tool can spit out an undergraduate thesis, how long until it can write an Econometrica?

Simon Williamson writes about being a software engineer watching ChatGPT accomplish a task flawlessly in 2023

I remember having two competing thoughts in parallel.

On the one hand, as somebody who wants journalists to be able to do more with data, this felt like a huge breakthrough. Imagine giving every journalist in the world an on-demand analyst who could help them tackle any data question they could think of!

But on the other hand… what was I even for? My confidence in the value of my own projects took a painful hit. Was the path I’d chosen for myself suddenly a dead end?

A friend of mine who works in bank regulation had the same thought several weeks ago. “If Claude can write the code that regulates these banks and make the reports and whatever why am I going to have a job? What am I going to do?”

To me, all of this seems a bit short-sighted. While it is true that if tool built on LLMs can automate large numbers of tasks, there is always more to do. There’s always more!

Suppose that we get large language models which are capable of solving any question currently asked in the whole field of economics today, meaning that many of the largest challenges facing the field are immediately solved through verifiable, automated output of LLMs. In my opinion we are far from this being possible, but just hypothetically.

Would we have “solved economics?” Would this actually be remotely close to understanding human interaction at all levels, or all possible means of exchange? Our macro models are so stylized that they often have a single good you eat and a single good you save with! Do we really think we are that close to solving anything?

I had a conversation with Leonid Kogan a number of years ago where he said to me, “I think that with modern macroeconomics we are kind of where medieval medicine was. We are still trying to balance the bodily humors via bloodletting with leeches.” To be clear, I think that this is one of the great reasons to work in economics; there is still so much to do. But there were always be more.

If you’ll indulge in a bit of an aside, one of the things I loved about my undergraduate work in music theory (at least as my advisor, Ed Gollin, taught it) is that it is the study of overdetermined systems. If you have never read any David Lewin and you are at all interested in music, I highly recommend it, check it out.

Lewin in the linked paper is trying to understand how it is possible that we listen to music in real time and experience a single physical phenomenon and yet this evokes a giant array experiences which vary person to person. How is it possible that we only experience the physical aspect of music instantly and in real, live time, and there exist many simultaneous layers to the music that can be perceived?

We may even experience several of these all at once, even while time flows on continuously. Further, there is recursive dependence on temporal context, so even though we hear each moment instantly our continuous experience and historical baggage brings to use context that further interacts with the experience of listening to a piece of music.

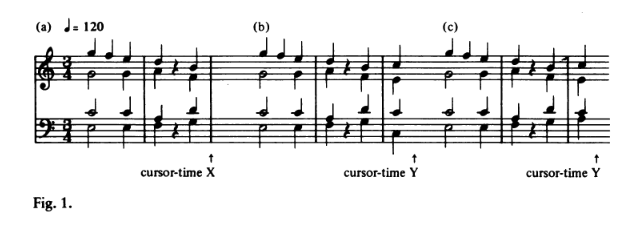

Here’s an example, reproduced from his essay:

Imagine a string ensemble playing the score shown by Figure 1(a), producing an acoustic signal which we shall call Signal(a). We ask, just what am I “perceiving” as I listen musically to that signal at the now-time corresponding to cursor-time X on the score. According to Husserl’s theory, what I am perceiving—let us call it Perception(a)—is a hugely complex network of things, things including other perceptions, their relations among themselves, and their relations to Perception(a) itself. I have, for example, perceptions (a1) ” harmony over the last beat”, (a2) “5th degree bass over the last beat.” and (a3), “7th degree in the melody over the last beat.” I perceive how the perceptions (a1), (a2), and (a3) are interrelating amongst themselves. I perceive how each of them is relating to my overall Perception(a) at cursor-time X. And I am retaining perceptions of how (a1), (a2), and (a3) each relate to yet earlier perceptions. […] “The C eight-three chord” is not an object of my perception at time X, at least not directly. The chord is perceived only indirectly, as an object of Perception(b), which is as yet perceived only as an object of Perception(a). It is not “the C chord” which is “very likely coming up in one beat’s time,” as I perceive things at X. Listening at that time to Signal(a), I do not form the idea of a disembodied C major chord coming up over the next beat as a context-free phenomenon. I do have a mental construct of a C major chord coming up over the next beat, but only in the context of a broader mental construct that is Perception(b).

In math or engineering we might call this an “inverse problem,” but unlike in engineering the goal of studying such a system is not to locate some kind of most likely input or answer, but instead to elucidate, unravel, and unroll the many layers of music. I like to call these “ways of hearing” a piece, which I may have stolen from Ed (I honestly don’t know). Whenever I was analyzing music, my goal was to formalize a system that explained my specific layered perceptual experience of the piece.

Borges writes in El Aleph:

I arrive now at the ineffable core of my story. And here begins my despair as a writer. All language is a set of symbols whose use among its speakers assumes a shared past. How, then, can I translate into words the limitless Aleph, which my floundering mind can scarcely encompass? Mystics, faced with the same problem, fall back on symbols: to signify the godhead, one Persian speaks of a bird that somehow is all birds; Alanus de Insulis, of a sphere whose center is everywhere and circumference is nowhere; Ezekiel, of a four-faced angel who at one and the same time moves east and west, north and south. (Not in vain do I recall these inconceivable analogies; they bear some relation to the Aleph.) Perhaps the gods might grant me a similar metaphor, but then this account would become contaminated by literature, by fiction. Really, what I want to do is impossible, for any listing of an endless series is doomed to be infinitesimal. In that single gigantic instant I saw millions of acts both delightful and awful; not one of them occupied the same point in space, without overlapping or transparency. What my eyes beheld was simultaneous, but what I shall now write down will be successive, because language is successive. Nonetheless, I’ll try to recollect what I can.

I bring this up, because this is a problem of infinite depth, there is no stopping point. While it may be true that something as trivial (in a cosmic sense) as “getting journal articles published” is a solvable game which is directly threatened by these kinds of automation, the broad pursuit of knowledge, experience, and explanation is simply unending. It’s amazing that we can make any progress on the problem at all in our finite lives. If you can’t come up with things to do, that is, as the kids say, a skill issue.